In 2009, the EU Committee of Regions adopted a

White Paper on Multi-Level Governance. During the public consultation of this document, I prepared the following opinion:

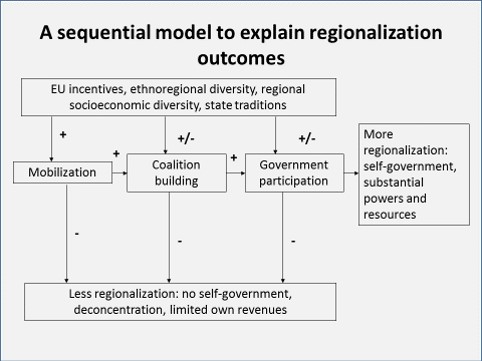

From a theoretical perspective, the most convincing strategy of institutional design would be to ensure a congruence between those affected by policies and those eligible to elect the political representatives who decide on these policies. Such a congruence of constituencies would create the best conditions for policymakers to be held accountable for their policies and thus strengthen the incentives for responsive policymaking. In contrast, an incongruence between those responsible for and those affected by a policy would provide incentives for unaccountable and unresponsive policymaking (e.g. negative external effects, moral hazard, freeriding).

The congruence principle would imply that public functions are assigned to the territorial level (jurisdiction) that can be expected to (a) perform these functions most effectively, (b) comprises all important stakeholders and addressees of a given policy. Most importantly, congruence would suggest avoiding the sharing of responsibilities for policies between different territorial levels, because power sharing arrangements may dilute responsibilities and thus public accountability.

I see the subsidiarity principle as detached from its communitarian and organicist connotations and merely as an evaluative instrument (a heuristic) to achieve a clear assignment of functions to territorial levels, starting from the smallest jurisdiction. In principle, one could of course also start from the largest jurisdiction and ask whether smaller jurisdictions have comparative advantages in performing functions.

Thus, if multilevel governance means joint or nested governance, democratic theory would expect accountability problems to emerge. However, there are policy issues that can be most effectively addressed if different tiers of government cooperate. To ensure a maximum degree of accountability and participation, cooperation on multi-level problems should take place on a voluntary basis, not within an institutional framework that makes actions taken by one tier of government dependent on the approval of other tiers. In my view, the essence of the “partnership” model of governance suggested by the White Paper (p. 11) is (a) an equal democratic status of local, regional, national and European tiers of government and (b) the voluntary cooperation among these different tiers. Voluntary cooperation presupposes a mutual recognition of the partner’s democratic legitimacy. As democratic legitimacy does not necessarily require a “thick” identitarian attachment of citizens to one tier of government but is ensured through participation and accountability mechanisms, the EU tier of government relies on independent sources of democratic legitimacy and qualifies as a partner of equal status.

I do not assume that the current allocation of public functions to tiers of government in the European system of multilevel governance maximizes congruence of constituencies and would thus be the most appropriate institutional arrangement with respect to accountability or participatory democracy. To improve and revise the design, the principles of congruence and voluntariness (partnership) would suggest the following sequence of guidelines:

All tiers of government should deliberate and decide whether a problem is best solved by one or several jurisdictions separately or whether it is a genuinely multi-level problem. Given the accountability and responsiveness advantages of separate-level policymaking, a separatory assignment of functions should be preferred if it is desired by one of the tiers. (This guideline would inter alia imply involving local and regional government in amendments of the Treaties.)

read more