Liberal democracy has been seriously questioned and challenged in Europe. To act against democratic backsliding in Hungary and other EU member states, EU institutions initially relied mainly on EU infringement procedures. The EU has complemented these instruments with a rule of law conditionality mechanism and developed procedures on how to suspend membership rights (Article 7, Treaty on the EU). The Council of Europe and its Venice Commission have elaborated an extremely valuable series of documents defining key principles and institutions of liberal democracy. However, these elements have not yet evolved into a coherent constitutional blueprint for a liberal democracy, not least because national institutional arrangements differ significantly.

Tag: Democracy Assessment

Demokratie im postkommunistischen EU-Raum. Erfolge, Defizite, Risiken

Springer Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2021 (Mitherausgeber: Günter Verheugen und Karel Vodička)

Wie resilient ist die Demokratie in Osteuropa? Mehrere Regierungen demontierten rechtsstaatliche Kontrollen und beschränkten die Meinungsvielfalt. Beflügelt von den Krisen der Europäischen Union, mobilisieren Populisten und Extremisten Unzufriedene. Korruptionsaffären und dubiose ökonomische Interessen scheinen die Politik zu beherrschen. Dieses Buch untersucht, inwieweit Akteurskonstellationen und gesellschaftliche Bedingungen illiberale Politiken in den postkommunistischen EU-Staaten begünstigen. Renommierte Länderexpert*innen analysieren Defizite, Erfolge und Risiken der demokratischen Entwicklung in den postkommunistischen EU-Mitgliedstaaten und in Ostdeutschland. Sie liefern ein systematisch vergleichendes und nuanciertes Gesamtbild – eine Generation nach den demokratischen Umbrüchen und im Blick auf Europas neue Gegensätze.

Towards a valid and viable measurement of SDG target 16.7

My chapter in: SDG16 Data Initiative. Global Report 2020, New York, 32-37

The UN Member States have set ten specific targets for Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16 , the promotion of just, peaceful and inclusive societies. Of these targets, target 16.7 aims at ensuring “responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels”. Among the 17 SDGs and the 169 targets defined to achieve the Goals, target 16.7 may be viewed as a key target because it focuses on political decision-making, which is a crucial prerequisite for all of the desirable policy outcomes defined in SDG 16 and in the other SDGs. This chapter discusses the official indicators for monitoring target 16.7 and argues that the Global State of Democracy Indices – a set of democracy measures developed by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) – can function as valid proxy indicators.

Rekindling Democracy’s Promise in Europe

An Op-Ed for “The European” and “Balkan Insight“, jointly written with A. Bekaj

A little more than 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the jubilation felt over the dawning of democracy in Central and Eastern Europe has dissipated. The region faces challenges that make the promise of democracy look like a mirage.

Over time, regimes in countries such as Poland, Hungary, Serbia and Bulgaria have taken steps to curtail civic space, undermine checks and balances and concentrate power in the hands of a few.

Conditions of Democratic Backsliding

Shop Talk at Pew Research Center, Washington DC

Democratic backsliding can be defined as the gradual weakening of checks on government and civil liberties by democratically elected governments. In my talk I discussed potential causal paths likely to trigger and support backsliding. By comparing episodes of democratic decline over time and with countries not affected by backsliding, I investigated the extent to which weaknesses of particular democratic institutions, economic crises, exposure to globalization, the presence of populist political actors and polarized political communication in a digital public sphere contribute to backsliding. My empirical analysis was based, amongst others, on the Digital Society Survey and the Global State of Democracy (GSoD) Indices, an set of composite indicators that measure democratic performance across 158 countries from 1975 to today.

The Quality of Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe

Contribution to “Democracy under Stress“, ed. by. P. Guasti and Z. Mansfeldová, Institute of Sociology, Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague 2018, 31-53.

The young democracies in East-Central and Southeast Europe have been particularly susceptible to the wave of populist, anti-establishment and extremist political forces that now challenge liberal democracy across the globe. These challengers claim to represent the opinion of the ordinary people against a political establishment that is portrayed as corrupt, elitist and controlled by foreign interests. Their polarizing and anti-pluralist ideological stances have contributed to a more confrontational political competition. Several countries have also seen “democratic backsliding”, an erosion of the institutions and mechanisms that constrain and scrutinize the exercise of executive authority. Illiberal policies have targeted opposition parties, parliaments, independent public watchdog institutions, judiciaries, local and regional self-government, mass media, civil society organizations, private business and minority communities. Incumbent elites have justified these policies as measures to strengthen popular democracy and to fulfill the promises of the post-1989 democratic transitions.

Can Responsiveness Substitute Accountability?

Lessons from the Central and East European Laboratory of Populist Democracy. A paper presented at the conference ” Totalitarian Reverberations in East-Central Europe”, Faculty of European Studies, Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, 26 October 2018.

Responsiveness characterizes a democratic process that „ induces the government to form and implement policies that the citizens want” (G. B. Powell). Populist parties advocate public policies that reflect the preferences of ordinary citizens, and their electoral success indicates that people believe their claims. Governing populist parties in Hungary, Poland and other Central and East European countries have systematically eroded institutions of democratic accountability, justifying these policies as measures to strengthen popular democracy and to fulfill the promises of the post-1989 democratic transitions. Although this erosion has been criticized as democratic backsliding and illiberal drift by scholars and international institutions, significant shares of voters continue to view it as steps towards a more responsive democracy.

Patterns of Democratic Backsliding

A paper for the ECPR General Conference, Hamburg, 25 August 2018, Panel 408: Same ingredients, different recipes: EU leverage and democratic backsliding in new member states and candidate countries

The subsequent economic and refugee crises have weakened the credibility of mainstream political parties in East-Central and Southeast Europe (ECSE) since prosperity and security no longer appear to be guaranteed consequences of European integration. The declining legitimacy of incumbents has provided opportunities for populist and anti-establishment mobilization. While these crisis-induced influences have been similar in all ECSE countries, the extent to which populist challengers have been able to win elections and form governments has varied significantly across countries. To explore these differences and assess the likelihood of populist electoral victories and subsequent illiberal policies in ECSE, the paper combines case studies of Hungary, Macedonia and Poland with a multivariate analysis of party systems, issue dimensions and cleavage configurations. It is argued that populist parties have attained political majorities through bipolar party competition, facilitated by congruent cleavages, particularly the congruence between sociocultural and EU-related cleavages. Based upon a comparison of the country cases, the paper discusses conditions that could constrain the illiberal erosion of democracy in ECSE.

Illiberal Drift and Proliferation

In recent years, the illiberal tendencies characteristic of several East-Central and Southeast European countries have taken their toll on nearly all segments of society, from opposition parties to parliaments and judiciaries, to oversight institutions, local and regional self-governing administrative organs, the media, NGOs, the private sector and minority groups as well. This process can best be described as “illiberal drift,” because key democratic institutions – free and competitive elections, political participation rights and individual liberties, separation of powers and rule of law – are not abolished or fundamentally questioned. Rather these institutions are, over time, re-interpreted and subject to changes that pull them increasingly further away from the understanding that led the democratization processes of the 1990s and the enlargement of the EU in the 2000s. In recent years, the dismantling and erosion processes in Hungary and Poland have raised particular international attention. However, illiberal thinking and acting have meanwhile proliferated to numerous states of East-Central and Southeast Europe.

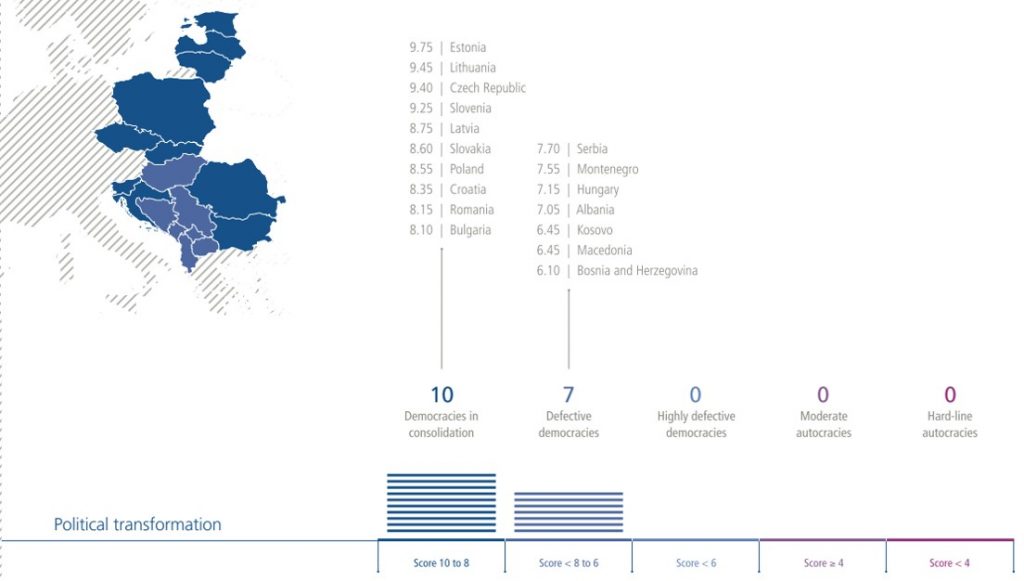

My regional report is part of the Transformation Index project, a global comparison and expert survey on democracy, market economy and governance in developing and postsocialist countries.

Download:BTI18_OMESOE

Crisis Trajectories and Patterns of Resilience in East-Central and Southeast Europe

The subsequent economic and refugee crises have questioned the promise of prosperity and security associated with European integration. Governments in East-Central and Southeast Europe struggled to bridge between the diverging policy expectations of voters on the one hand, international economic and political actors on the other. The weakened credibility of mainstream political parties provided opportunities for populist and anti-establishment mobilization. While these crisis-induced influences have been similar in all countries of the region, the extent to which populist challengers have been able to win elections and implement their preferred policy preferences has varied significantly across countries.

In my paper, I analyze the conditions and constellations that account for the resilience of countries with regard to the domestic political consequences of the European crises. I argue that populist challenger parties benefit from bipolar competition because they use polarizing frames of people versus elites to mobilize electoral support. The fragmentation and polarization of party systems reflect the nature of the electoral system and the configuration of cleavages in society. A majoritarian electoral system and congruent cleavages have supported the emergence of bipolar party system in Hungary and Poland. In contrast, cross-cutting cleavages tend to generate and sustain multi-polar party systems. These party systems facilitate the entry of new parties, but have posed obstacles to new parties trying to broaden and consolidate their constituencies. To assess the intersection or congruence of cleavages, the paper studies the configuration of differences among parties on salient policy issues.

See also: