Liberal democracy has been seriously questioned and challenged in Europe. To act against democratic backsliding in Hungary and other EU member states, EU institutions initially relied mainly on EU infringement procedures. The EU has complemented these instruments with a rule of law conditionality mechanism and developed procedures on how to suspend membership rights (Article 7, Treaty on the EU). The Council of Europe and its Venice Commission have elaborated an extremely valuable series of documents defining key principles and institutions of liberal democracy. However, these elements have not yet evolved into a coherent constitutional blueprint for a liberal democracy, not least because national institutional arrangements differ significantly.

Tag: Concepts

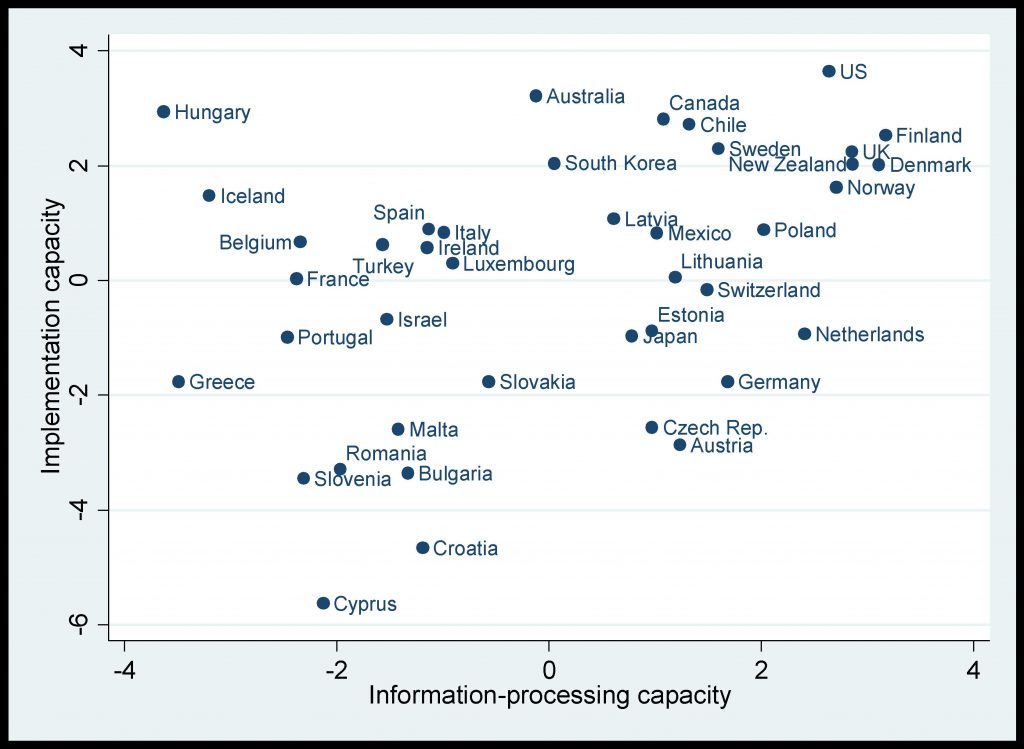

Towards a valid and viable measurement of SDG target 16.7

My chapter in: SDG16 Data Initiative. Global Report 2020, New York, 32-37

The UN Member States have set ten specific targets for Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16 , the promotion of just, peaceful and inclusive societies. Of these targets, target 16.7 aims at ensuring “responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels”. Among the 17 SDGs and the 169 targets defined to achieve the Goals, target 16.7 may be viewed as a key target because it focuses on political decision-making, which is a crucial prerequisite for all of the desirable policy outcomes defined in SDG 16 and in the other SDGs. This chapter discusses the official indicators for monitoring target 16.7 and argues that the Global State of Democracy Indices – a set of democracy measures developed by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) – can function as valid proxy indicators.

Demokratisierungsprozesse und ihre Akteure

Ein Überblick zum Stand der Theoriebildung

in: Protest im langen Schatten des Kreml. Aufbruch und Resignation in Russland und der Ukraine, hg. v. O. Zabirko und J. Mischke, Stuttgart: Ibidem 2020, 17-36

Seit den Übergängen zur Demokratie in Ostmitteleuropa 1989/90 ist eine umfangreiche sozialwissenschaftliche Literatur zur Demokratisierung entstanden. Diese Arbeiten haben die Bedingungen, Verlaufsmuster und Ergebnisse von Demokratisierungsprozessen rekonstruiert und im Ländervergleich analysiert. Sie sind bisher jedoch noch nicht so weit fortgeschritten, dass man eine bestimmte Anzahl von Akteurkonstellationen und Strategien benennen könnte, die für die Errichtung und Konsolidierung demokratischer Institutionen notwendig und hinreichend sind. Während modernisierungstheoretische Studien die für eine stabile Demokratie erforderlichen ökonomischen und gesellschaftlichen Strukturbedingungen hervorhoben, betrachteten Studien zu den lateinamerikanischen und südeuropäischen Demokratie-Übergängen Abkommen (“Pakte”) zwischen Reformern innerhalb der herrschenden Elite und moderaten Oppositionsführern als die entscheidenden Weichenstellungen für die neue Demokratie. Die spätere Forschung argumentierte dagegen, dass stabile Demokratien sich nicht aus Kräftegleichgewichten bildeten, sondern dort, wo demokratische politische Akteure über die Kräfte des autoritären Regimes triumphierten.

The Quality of Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe

Contribution to “Democracy under Stress“, ed. by. P. Guasti and Z. Mansfeldová, Institute of Sociology, Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague 2018, 31-53.

The young democracies in East-Central and Southeast Europe have been particularly susceptible to the wave of populist, anti-establishment and extremist political forces that now challenge liberal democracy across the globe. These challengers claim to represent the opinion of the ordinary people against a political establishment that is portrayed as corrupt, elitist and controlled by foreign interests. Their polarizing and anti-pluralist ideological stances have contributed to a more confrontational political competition. Several countries have also seen “democratic backsliding”, an erosion of the institutions and mechanisms that constrain and scrutinize the exercise of executive authority. Illiberal policies have targeted opposition parties, parliaments, independent public watchdog institutions, judiciaries, local and regional self-government, mass media, civil society organizations, private business and minority communities. Incumbent elites have justified these policies as measures to strengthen popular democracy and to fulfill the promises of the post-1989 democratic transitions.

Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftsordnungen

Abstract

Die Analyse der Zusammenhänge zwischen wirtschaftlicher und gesellschaftlicher Ordnung hat in Politik- und Wirtschaftswissenschaft nicht nur eine lange Tradition, sondern erlebt derzeit auch eine lebhafte Renaissance. Das vorliegende Kapitel gibt einen Überblick über die früheren und heutigen Beiträge zu dieser Thematik. Der Schwerpunkt liegt dabei auf Forschungen an der Schnittstelle von Wirtschafts- und Politikwissenschaft. Darüber hinausgehend bemühen wir uns, eine Erklärung dafür zu finden, warum das Interesse an dem hier behandelten Thema im historischen Zeitablauf auffälligen Schwankungen unterliegt. Unsere diesbezügliche These lautet: Immer dann, wenn das Verhältnis von politischem und ökonomischem System dynamischen Veränderungen unterliegt, steigt das Interesse am Zusammenhang zwischen Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftsordnungen; immer dann, wenn das Verhältnis der beiden gesellschaftlichen Subsysteme relativ stabil ist, beschäftigen sich Politikwissenschaftler und Ökonomen eher damit, was innerhalb „ihres“ jeweiligen Systems vor sich geht.

Einleitung

Der vorliegende Beitrag verfolgt eine doppelte Zielsetzung. Zum einen wollen wir überblicksartig darstellen, wie Politikwissenschaftler und Ökonomen jeweils über das Themengebiet „Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftsordnungen“ denken und schreiben. Zum anderen – und darauf liegt unser Schwerpunkt – wollen wir jene „polit-ökonomischen“ (also an der Schnittstelle beider Disziplinen angesiedelten) Theorieansätze näher beleuchten, die sich mit den Zusammenhängen zwischen Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftsordnung befassen. Solche Ansätze haben in Politikwissenschaft wie Volkswirtschaftslehre nicht nur eine lange Tradition, wie etwa in der klassischen Politischen Ökonomie (Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx), im Historismus oder in der deutschen Ordnungsökonomik, die sich vor allem mit dem Problem der „Interdependenz“ der politischen und wirtschaftlichen Ordnung befasste. Sondern derartige Ansätze erleben derzeit durch Autoren wie Daron Acemoglu und James A. Robinson (2006; 2012) oder Douglass C. North, John J. Wallis und Barry R. Weingast (2009) derzeit auch eine lebhafte Renaissance. Unsere These lautet: Dieses Revival polit-ökonomischen Theoretisierens ist kein Zufall, sondern dem Umstand geschuldet, dass wir in einer historischen Phase leben, in der das Verhältnis von Wirtschaft und Politik besonders dynamischen Veränderungen unterliegt. Diese Veränderungsdynamik lenkt die Aufmerksamkeit sowohl von Politik- als auch von Wirtschaftswissenschaftlern an die Schnittstellen der Systeme. Grundsätzlich scheint zu gelten: Immer dann, wenn das Verhältnis von politischem und ökonomischem System „in Bewegung“ ist, intensiviert sich auch die inter-disziplinäre Analyse der auf diese beiden Erkenntnisobjekte spezialisierten Disziplinen; immer dann, wenn das Verhältnis der beiden gesellschaftlichen Subsysteme stabil ist, beschäftigen sich Politikwissenschaftler und Ökonomen eher damit, was innerhalb „ihres“ jeweiligen Systems vor sich geht.

Das Kapitel gliedert sich im Wesentlichen chronologisch wie folgt: Im folgenden zweiten Abschnitt behandeln wir die Ko-Evolution von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft und die wissenschaftliche Analyse ihres Verhältnisses von der Industriellen Revolution bis zur Großen Depression der 1930er Jahre. Der dritte Abschnitt befasst sich mit den sozialistischen Ordnungen und der Systemtransformation. Der vierte Abschnitt ist dem „Goldenen Zeitalter“ des wohlfahrtstaatlichen Kapitalismus (1960er bis 1980er Jahre), der Diversität marktwirtschaftlicher Ordnungen und der Globalisierung gewidmet. Der fünfte Abschnitt schließlich behandelt die heutigen Schnittstellendiskurse über wirtschaftliche und gesellschaftliche Ordnungen.

(…)

Aktuelle Schnittstellendiskurse: Von disziplinären zu transdisziplinären Bruchlinien?

Im heutigen interdisziplinären Diskurs über Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftsordnungen lassen sich zwei Strömungen unterscheiden, die in gewisser Weise an die beiden Erklärungsansätze institutionellen Wandels von Douglass C. North anschließen. Während die in den 1960er und 1970er Jahren entstandene „Neue Institutionenökonomik“ heute weitgehend von der Mikroökonomik absorbiert worden ist, hat sich ab der zweiten Hälfte der 1990er Jahre eine ökonomische Denkrichtung etabliert, die sich aus einer Makroperspektive mit Institutionen als Determinanten von Wachstum und Entwicklung beschäftigt (etwa: Hall/Jones 1999; Rodrik/Subramanian/Trebbi 2004). Charakteristisch für diesen Ansatz ist erstens ein relativ enger Institutionenbegriff, der sich weitgehend auf formelle Institutionen (wie etwa Eigentumsrechte, die Rule of Law, das Wahlrecht) beschränkt, und zweitens ein Streben nach analytischer Rigorosität, das sich in einer stark formalisierten Sprache und dem Bestreben ausdrückt, die aufgestellten Hypothesen ökonometrisch zu überprüfen. Vor allem dank der für diese Richtung wegweisenden Beiträge des Ökonomen Daron Acemoglu und des Politologen James A. Robinson hat sich hier ein genuin polit-ökonomischer Diskurs entwickelt, im Rahmen dessen Ökonomen und Politologen auf Grundlage einer einheitlichen Methodik forschen. Das wohl bisher wichtigste Ergebnis dieser in normativer Hinsicht zumeist eher liberal ausgerichteten Forschung besteht in der Neuformulierung der bereits bei den Autoren der Freiburger Schule um Franz Böhm und Walter Eucken, bei Douglass C. North und bei Mancur Olson thematisierten Interdependenz von wirtschaftlicher und politischer Ordnung. Um diesen Zusammenhang zu verdeutlichen, unterscheiden Acemoglu und Robinson in ihrem jüngsten Buch „Why Nations Fail“ (2012) zwischen „extraktiven“ und „inklusiven“ Ordnungen. Der entscheidende Punkt lautet dabei: Dort, wo politische Herrschaft monopolisiert ist, liegt es regelmäßig im Interesse der Herrscher, Innovationen gezielt zu unterdrücken, weil die damit verbundene „kreative Zerstörung“ (Schumpeter) nicht nur wirtschaftliche Pfründe, sondern auch die Herrschaft der politischen Elite destabilisieren könnte.

Der zweite interdisziplinäre Diskurs kreist stärker um jene informellen Bestimmungsgründe von Wandlungsprozessen wie mentale Modelle, historische und kulturelle Vermächtnisse und religiöse Prägungen, wie sie bereits in den Historischen Schulen, im älteren Institutionalismus und bei Douglass C. North in seinem späteren Werk behandelt worden waren. Nachdem es auch in der Ökonomik in den 1990er Jahren eine Diskussion um die Bedeutung „weicher“ Faktoren für institutionellen Wandel gegeben hatte (etwa Greif 1994; Denzau/North 1994; Keefer/Knack 1997) wurde er in den 2000er Jahren immer stärker von den hier erstgenannten Ansätzen überlagert, die den entscheidenden Vorteil haben, kompatibler mit den in der Ökonomik vorherrschenden quantitativen Methoden zu sein. So waren es vor allem Politikwissenschaftler und Soziologen, die – vor allem im Rahmen der bereits erwähnten „New Political Economy“ – den Diskurs über die Bedeutung informeller Institutionen für Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftsordnungen fortführten (stellvertretend: Streeck/Thelen 2005). Als ein besonders dynamischer Zweig hat sich dabei die Diskussion über „Ideen und institutionellen Wandel“ erwiesen, die bisweilen zu der Forderung geführt hat, ein gesondertes Forschungsfeld, den sogenannten „ideationalen“ oder „konstruktivistischen“ Institutionalismus zu etablieren (Blyth 2002; Beland/Cox 2011; Hay 2006; Schmidt 2008). Auch in diesem qualitativ-historisierenden Zweig institutioneller Forschung zeigt sich in allerjüngster Zeit zumindest die Tendenz ab, dass Ökonomen und Sozialwissenschaftler Fächergrenzen überwinden und einen gemeinsamen Diskurs etablieren. Ein Anzeichen dafür ist die 2014 erfolgte Gründung des „World Interdisciplinary Network for Institutional Research (WINIR)“. Bemerkenswert ist, dass die Initiative zur Gründung des Netzwerks von dem heterodoxen Institutionenökonomen Geoffrey Hodgson ausging – wohl der Einsicht folgend, dass das eigene Forschungs-programm innerhalb der eigenen Disziplin immer weniger anschlussfähig ist. Und Dani Rodrik, einer der derzeit bedeutendsten Entwicklungsökonomen hat sich mit einem ebenfalls aus dem Jahr 2014 stammenden Papier „When Ideas Trump Interests: Preferences, Worldviews, and Policy Innovations“ eindeutig an den sozialwissenschaftlich dominierten Diskurs über „weiche Faktoren“ wirtschaftlicher Entwicklung angeschlossen.

Angesichts der hohen Tempos des weltweit zu beobachtenden institutionellen Wandels und aufgrund der jüngsten Krisenerfahrungen ist die Frage nach dem Zusammenhang zwischen wirtschaftlicher und politischer Ordnung heute sowohl für Wirtschafts- als auch Politikwissenschaftler hochgradig aktuell. Das gilt offenkundig auch für den Gegenstand des ersten Methodenstreits (vgl. Louzek 2011), die von Walter Eucken so bezeichnete „Antinomie“ zwischen deduktiv-theoretischer-quantitativer und verstehend-historisierend-qualitativer Erforschung gesellschaftlicher Ordnungen und ihres Wandels, von denen die erste Richtung stärker nach allgemeingültigen Gesetzmäßigkeiten fragt und die zweite eher an den spezifischen Bestimmungsgründen institutionellen Wandels interessiert ist. Aus unserer Sicht ist es faszinierend zu beobachten, dass die Grenzen zwischen den jeweiligen Lagern zunehmend nicht mehr zwischen den Disziplinen verlaufen, sondern mitten durch sie hindurch. Diese Beobachtung muss aber dahingehend abgeschwächt werden, dass zum heutigen Zeitpunkt das erstgenannte Lager innerhalb der Ökonomik eindeutig dominant ist und dass die Volkswirtschaftslehre diesen Diskurs bei aller Interdisziplinarität in methodischer Hinsicht klar dominiert. Und innerhalb des zweitgenannten, historisierend-qualitativen Lagers gilt umgekehrt, dass die Ökonomen in diesem Diskurs rein zahlenmäßig in der Minderheit sind und die vorherrschenden Methoden – jedenfalls dann, wenn man von der Methodologie der modernen VWL ausgeht – eher als sozial- denn als wirtschaftswissenschaftlich zu charakterisieren sind.

Festzuhalten bleibt jedenfalls, dass der interdisziplinäre Diskurs über Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftsordnungen heute mit großer Intensität geführt wird. Das Interesse an den Zusammenhängen zwischen Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft findet neben der reinen Forschung auch darin seinen Ausdruck, dass sich interdisziplinäre Studienprogramme an den Schnittstellen von Philosophie, Politik und Ökonomik weltweit wachsender Beliebtheit erfreuen.

Core Executives in Central Europe

Core executives have become increasingly important political actors and arenas due to several interlinked developments affecting both states and societies. Modernisation has weakened the ties between political parties and voters, making parties more dependent on state resources and, in particular, access to government. Since the political process has become more dominated by media communication, political controversy tends to be framed between chief executives and rival political leaders. Global economic integration has narrowed the policy discretion of nation states and fostered the spread of non-majoritarian institutions entrusted with regulatory functions. These trends have been associated with the growing weight of policy output as a source of legitimacy, in contrast to “input legitimacy” derived from democratic elections. Among the three branches of state power, executives control most of the tools available to influence policy outputs and the interventions of both domestic and international regulatory agencies. The crisis and politicisation of European integration have further enhanced the salience of national (chief) executives compared to national legislatures and supranational institutions. As a result, many of the choices characterising politics and policymaking are now made or shaped at the centres of executives.

This chapter discusses the ‘core executive’ both as an empirical field of actors, institutions, and behavioural practices at the centres of Central European governments and as a theoretical concept formulated to study this field. The term ‘core executive’ was initially proposed by Dunleavy and Rhodes (1990) to describe the centre of the British government from a functional perspective. The core executive comprises ‘all those organizations and procedures which coordinate central government policies, and act as final arbiters of conflict between different parts of the government machine’ (Rhodes, 1995, 12, Dunleavy and Rhodes, 1990). In the United Kingdom, these functions are performed by ‘the complex web of institutions, networks and practices surrounding the prime minister, cabinet, cabinet committees and their official counterparts, less formalised ministerial ‘clubs’ or meetings, bilateral negotiations and interdepartmental committees’, including the coordinating departments at the centre of government (Rhodes, 1995, 12). The notion of a core executive represents a conceptual innovation insofar as it

This chapter discusses the ‘core executive’ both as an empirical field of actors, institutions, and behavioural practices at the centres of Central European governments and as a theoretical concept formulated to study this field. The term ‘core executive’ was initially proposed by Dunleavy and Rhodes (1990) to describe the centre of the British government from a functional perspective. The core executive comprises ‘all those organizations and procedures which coordinate central government policies, and act as final arbiters of conflict between different parts of the government machine’ (Rhodes, 1995, 12, Dunleavy and Rhodes, 1990). In the United Kingdom, these functions are performed by ‘the complex web of institutions, networks and practices surrounding the prime minister, cabinet, cabinet committees and their official counterparts, less formalised ministerial ‘clubs’ or meetings, bilateral negotiations and interdepartmental committees’, including the coordinating departments at the centre of government (Rhodes, 1995, 12). The notion of a core executive represents a conceptual innovation insofar as it

(1) focuses on neutral functions rather than specific institutions like the prime minister or cabinet which may convey normative connotations and cultural bias;

(2) goes beyond a formal institutional analysis to investigate the empirical practice and resources of policy coordination, including both its political and administrative dimensions; and

(3) reflects the fragmented network of institutions that emerged from neoliberal reforms of government and substituted the traditional framework of cabinet government.

Replacing hierarchic, Weberian models of central government by market mechanisms, negotiations, and networks as modes of governance, these reforms are viewed as part of a broader ‘hollowing-out of the state’, a process that has also been driven by growing international interdependencies, the privatisation of public services and devolution (Rhodes, 1994). As a consequence, the spatial metaphor ‘core’ seems more appropriate than ‘top’, and heads or centres of government now appear to be more aptly characterised by their coordination and arbitration functions than by ‘instructing’ or ‘ordering’. The notion of political power underlying the concept of the core executive is relational and contingent (Rhodes and Tiernan, 2015, Elgie, 2011): in order to achieve their goals, prime ministers and core political actors depend on other actors and must exchange resources such as authority, expertise or money with them (Rhodes, 1997, 203).

Apart from these assumptions, the concept of the core executive initially did not bear any implications for the likely or desirable distribution of power, the prevalent modes of governance, or the roles of political actors in central government. This indeterminacy has facilitated its diffusion from the original British context to other Westminster systems as well as to continental European and even to presidential systems of government (Helms, 2005, Weller et al., 1997). However, the ‘essential malleability of the term “core executive” is [also] the reason why its use has become de rigueur. It is a wonderfully convenient term. The result, though, is that the universe of “core executive studies” includes a great deal of work that could, quite happily, use a different term and have no less analytical purchase.’(Elgie, 2011, 72)

The remainder of this chapter distinguishes two paradigms that have shaped core executive studies focusing on Central Europe and reflect the recent history of the region: transition and Europeanisation. A third paradigm of ‘executive governance’ is suggested as a perspective for future work. The main argument of the chapter is that the trend towards centralised executive authority in several Central European countries suggests complementing the analysis of institutional arrangements with a broader analysis of governance. Such an approach would relate institutions to policies and their outcomes, highlighting possible drawbacks of centralisation and trade-offs between different functions or policy objectives.

References

Dunleavy, P. and R. A. W. Rhodes (1990) ‘Core Executive Studies in Britain’, Public Administration, 68(1), pp. 3-28.

Elgie, R. (2011) ‘Core Executive Studies Two Decades On’, Public Administration, 89(1), pp. 64-77.

Helms, L. (2005) Presidents, Prime Minister and Chancellors. Executive Leadership in Western Democracies. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rhodes, R. A. (1995) ‘From Prime Ministerial Power to Core Executive’, in Rhodes, R.A. & P. Dunleavy (eds) Prime Minister, Cabinet and Core Executive. London: Macmillan, pp. 11-37.

Rhodes, R. A. (1994) ‘The Hollowing Out of the State: The Changing Nature of the Public Service in Britain’, The Political Quarterly, 65(2), pp. 138-151.

Rhodes, R. A. (1997) ‘”Shackling the Leader?”: Coherence, Capacity and the Hollow Crown’, in Weller, P., H. Bakvis & R.A. Rhodes (eds) The Hollow Crown. Countervailing Trends in Core Executives Transforming Government. Houndsmill, Basingstoke: Macmillan, pp. 198-223.

Rhodes, R. A. and A. Tiernan (2015) ‘Executive Governance and its Puzzles’, in Massey, A. & K. Miller (eds) International Handbook of Public Administration and Governance. Chelmsford: Edward Elgar, pp. 81-103.

Weller, P., H. Bakvis and R. A. Rhodes (eds) (1997) The Hollow Crown. Countervailing Trends in Core Executives. Houndsmill, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

BTI 2018 Kick-Off and Concept Paper

BTI is a global expert survey on the quality of democracy, market economy and governance, now in its eighth edition (!) scheduled for publication in 2018. Questionnaires will be sent to country experts at the end of October. The submission of country reports will trigger off an elaborate procedure of reviewing, revising, calibrating, editing and lesson-drawing, keeping us busy throughout the next year.

The meeting was a first occasion for Peter Thiery and me to present the draft of a comprehensive paper that situates the concepts guiding the BTI in the scholarly literatures on democratic theory, democratization, policy reform, good governance, economic transformation and aid effectiveness. Our paper also uses unpublished data from the BTI production process to evaluate the validity of the measurement and aggregation techniques underlying the composite indicators in the BTI dataset. Author-reviewer differences are studied across subsequent BTI editions. Various statistical models are constructed to assess the impact of changes among authors, reviewers and coordinators and to compare the effects of different aggregation rules. We plan to complete and publish the paper during the next months.

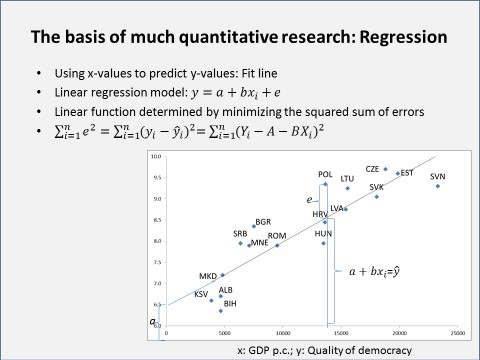

Policy Analysis and Policy Evaluation

To upgrade their research capacity, think tanks need access to methodological and conceptual tools that have recently been developed by researchers in the field of policy analysis and evaluation. My three-day workshop with Belgrade Open School provided an overview on rationalist and institutionalist approaches of policy analysis, focusing on examples from Europeanization studies. Notions of causation and strategies to deal with confounding causes formed the basis of our discussion on evaluation methods. The workshop also included an introduction to regression and factor analysis, two key tools of empirical policy research.

Founded in 1993, BOS has become one of Serbia’s leading civil society organisations for post-graduate training and public policy advocacy.

As a non-partisan and non-profit organization, BOS strengthens human resources, improves the work of public institutions and organisations, develops and advocates public policies in order to develop better society based on freedom, knowledge and innovation.

As a non-partisan and non-profit organization, BOS strengthens human resources, improves the work of public institutions and organisations, develops and advocates public policies in order to develop better society based on freedom, knowledge and innovation.

Methodology of Social Science Research

A full day of teaching with the staff of Ukraine’s leading independent think tank for International Relations, the Institute of World Policy. The main themes were:

1. Research design / causation, theory building;

2. Conceptualization and measurement

3. Qualitative and quantitative methods

4. Evaluating policies

Video clips available here

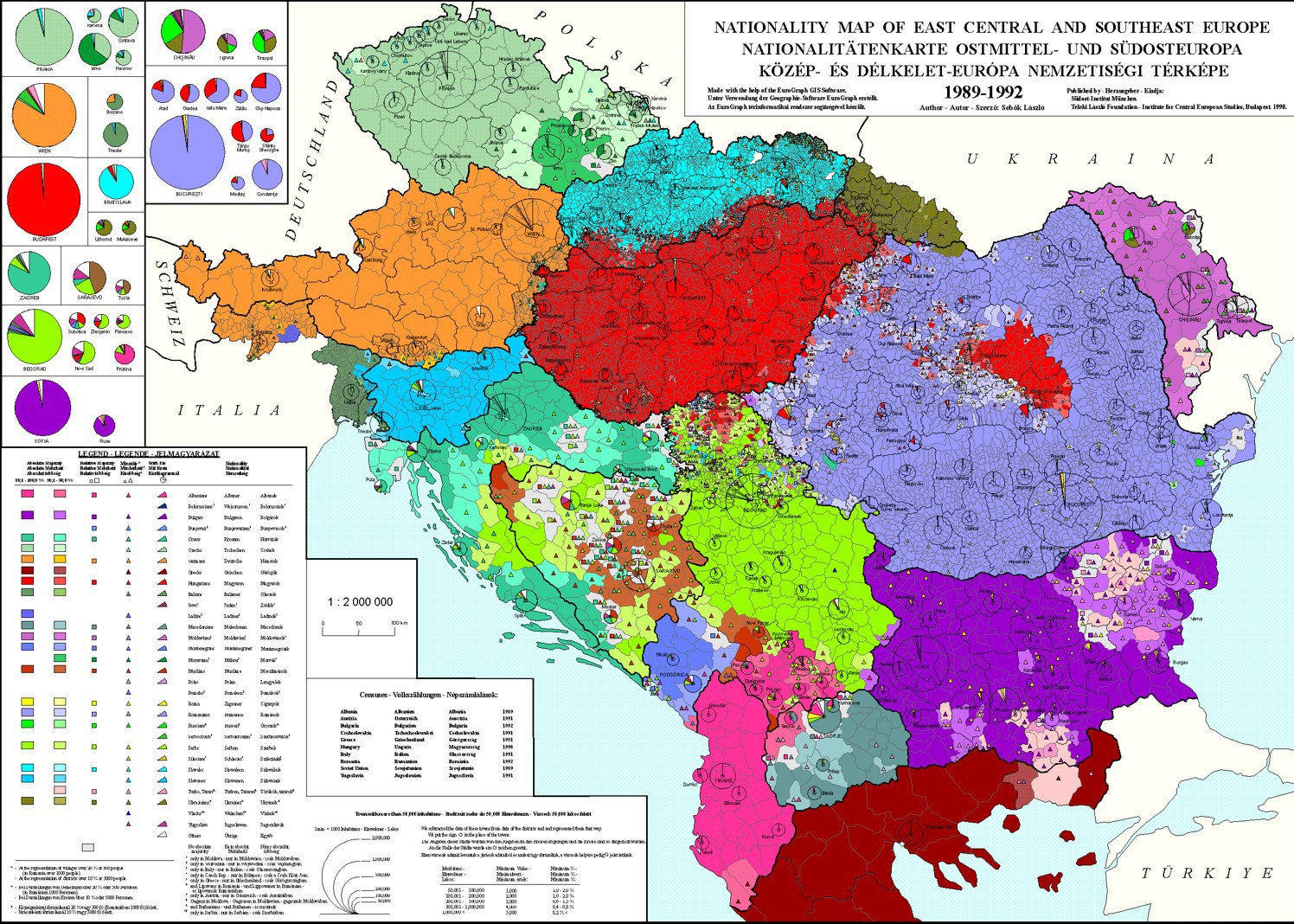

Ethno-Regional Diversity and Political Integration in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe has been shaped by historically late state and nation building. Due to this trajectory, questions of state identity and cohesion have acquired persisting political relevance. Ethnopolitical conflicts have led to the disintegration of all three state socialist federations. Ethnopolitical cleavages structure party systems in the new nation states of Eastern Europe, particularly where they are related to persisting ethnoregional diversity.

The course discussed the political integration of ethnoregional diversity in connection with the territorial restructuring of states which occured in the context of public administration reform, the consolidation of peace agreements and the preparation for accession to the European Union. Drivers, paths and outcomes of regionalization processses were compared.